You’ve just been to your doctor, during the appointment they listened to your heart with a stethoscope. A few hmms and then they tell you, “I think I hear a murmur, nothing to worry about, but we should get it checked out”. They refer you for an echo and then that’s it. Appointment over. Off you go with this new information and the worry that accompanies it.

What’s your first step? Google? Facebook? WebMD?

How do you know what information to trust?

Well, how about talking with a specialist in this exact topic? I’m a cardiac physiologist, with a specialism in the structures of the heart and how they work. I use ultrasound to look at your heart. It really is quite a spectacular sight, your heart on the screen. And I love nothing more that showing you just what I see and what it all means to you. Let’s talk through this murmur together.

What is a heart murmur?

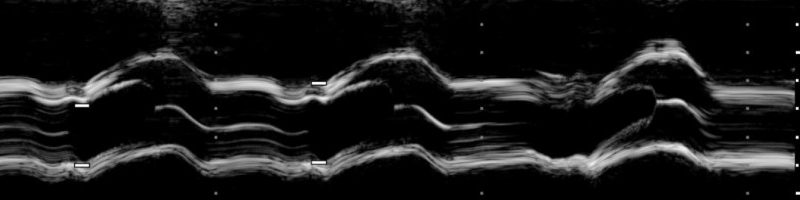

When your doctor listened to your heart through the stethoscope, they were listening to the sounds of your blood flowing through the different sections of your heart. In a normal healthy heart, there are two sounds. Commonly known as the lub and the dub. These sounds are caused by the opening and closing of the heart valves. The sound of the blood pumping between the different sections of your heart is not usually audible. So, a heart murmur can be the result of either the valve sounds being unusual or extra sounds caused by the abnormal flow of blood through the heart. These sounds can be difficult to hear, and it is certainly a skill to be able to tell the difference between them and even more of a skill to know how to interpret them. Listening through a stethoscope cannot accurately determine the actual cause of the abnormal sound or the severity of said cause. So, you have been referred for an echocardiogram (echo). This is an ultrasound of your heart. Using it we can see the structures of your heart, we can see how they move, how the heart pumps and we can see and measure how the blood flows through the heart. If there is an abnormality, we see it, measure it, and determine whether there is anything you need to be concerned about. This is how we assess a murmur.

There are three main causes of heart murmurs.

- Leaking heart valve

- A heart valve that doesn’t open properly

- Nothing at all (*we’ll get to this!)

The first two causes can occur in degrees of severity. From completely insignificant to severe and everything in between. The echo will let us identify the cause and the severity [1]

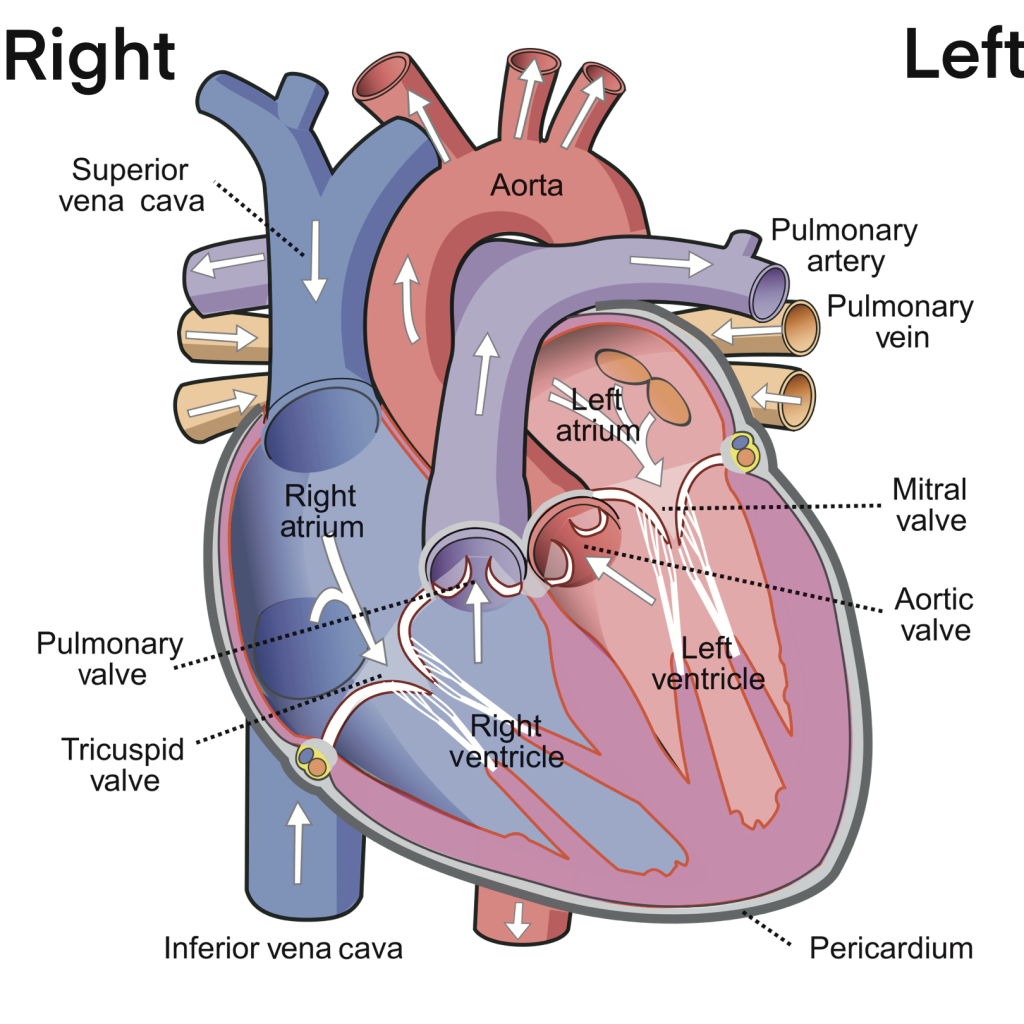

Heart Anatomy

Let’s have a quick look at the anatomy of the heart

Source: Wikipedia [2]

The heart is usually described as having a left side and right side. The left side is responsible for pumping fresh oxygen-rich blood around the body, the right side is responsible for pumping used blood to the lungs to collect oxygen. Each side of the heart has two heart valves. A valve separating the top and bottom chambers, the mitral and tricuspid valves, and a valve connecting the heart to the main body arteries, the aortic and pulmonary valves. Valves are comprised of thin collagen leaflets in varying configurations depending on where in the heart they are. Some valves have two leaflets, others have three. It is these leaflets that do a great job of making sure blood flows through the heart at the correct speed, pressure, and direction.

When it comes to murmurs, we know they can be caused by a leak or by the valve not opening properly.

Valves

Let’s talk first about the “nothing at all”. Sometimes, when a doctor is listening to your heart, they have a very specific idea of what the heart sounds like. If the sounds of your heart do not match this ideal, then your doctor may think you have a murmur. However, no two people are exactly alike, not even identical twins [3], and hearts sound different in every body. When an echo is performed there can be absolutely no cause found for a murmur. In these cases, we conclude that the murmur is likely due to how forcefully the heart pumps blood around the heart. This is called a benign flow murmur. They usually occur in children and young people. These murmurs do not require treatment and people live long and healthy lives. It is, however, important to note this finding in the medical records to prevent further unnecessary testing or increased anxiety in the patient. People with benign flow murmurs should have no restrictions on their daily lives [4].

Firstly, and this is very important, most people have a heart valve that leaks a tiny bit. And by a tiny bit, I mean a dribble, completely and utterly insignificant. These tiny leaks are normal and cause no trouble whatsoever. Sometimes they can be heard via the stethoscope and labelled as a murmur. If a tiny leak through one of your heart valves is all that is noted on your scan, then we can happily say there is absolutely nothing to be concerned about. You can go on your way, reassured that the murmur is nothing to worry about [5].

The most common cause of a valve abnormality is age. As we get older, the leaflets of the valves can get thicker and less able to keep blood flowing in the right direction [6]. However, sometimes a valve can become damaged by an illness, such as an infection [7] or a long term condition such as Lupus [8] or kidney disease [9].

Damage to a heart valve can cause it to leak more than can be considered insignificant, or it can cause the valve to stop opening properly, restricting how much blood can get through it. And sometimes, you can have both, a restriction, and a leak.

A valve leak or restriction is usually graded by severity. We usually label them as mild, moderate, and severe. And this helps guide the doctor’s treatment recommendations. We assess a leaky valve by how much blood leaks back through the valve and we assess a restricted valve by how much blood can go through it. The degree to which the valve is leaking or restricted is important because it can put pressure on the rest of the heart to try and compensate [10].

Let’s have a look at what each level means and what is usually the recommended course of treatment.

Mild: Mild leaks or restrictions very rarely cause any symptoms. We look at structure of the leaflets and how well they move. We also look to see if the rest of the heart is working normally. Usually in mild valve disease, the rest of the heart is not required to compensate. Usually there are no symptoms associated with mild valve disease. So the usual course of action is to do a monitoring scan every couple of years just to make sure it stays mild. The important thing to remember is you have likely had this for quite a while, without being bothered by it, so there really is nothing to be worried or anxious about. Make sure you attend your follow up scan and carry on with your life as normal. If in the time between scans, you start to experience symptoms, such as breathlessness, palpitations, swelling in the ankles, then please go back to your doctor to be assessed again [1] [10]

Moderate: This is where a level where we start to think about treatment and keeping a closer eye on things. With moderate valve disease, you may not have symptoms at all, or you may experience symptoms of mild breathlessness when you exert yourself, you may feel palpitations in your chest, or maybe you have episodes of your heart racing, your ankles may swell up throughout the day. This is all important information that you must tell your doctor. It will help them to know how to treat you. Usually, at this stage, we would just keep an eye on things. You will probably have another scan in about a year, maybe a little sooner if you are having symptoms. You may be prescribed some medications to help reduce any symptoms you experience and some of the medications can help lower the chance of the valve getting worse. It is really important that you take your medications as prescribed. Don’t stop taking any of your medications without talking to your doctor. If a medication doesn’t agree with you, and side effects are no fun, then talk to your doctor. There is almost always an alternative you can try that may be better suited. Overall, having moderate valve disease is nothing to be sniffed at, but is also usually nothing to be anxious about. Remember to keep your appointments, take any medications prescribed to you and let your doctor know if anything changes with your symptoms. Otherwise, you carry on with life as normal, and don’t let it interfere with your daily activities [1] [10].

Severe: This is the level of valve disease where we start to think about fixing it. The rest of your heart is usually trying to compensate for the abnormal valve and is starting to become damaged in other parts. The muscle of your heart can sometimes get thicker as a result of having to work harder. Sometimes, the heart cannot cope with the extra hard work, and it becomes weaker and unable to pump properly. Usually at this point you will have symptoms of breathlessness, palpitations, swelling ankles and sometimes even chest pains. These symptoms will be having an impact on your day-to-day life. Of course, we want to help stop all of this from getting any worse. Most of the time, by fixing the valve, the rest of the heart can recover and go back to pumping properly. Fixing the valve is something that should happen sooner rather than later. You will be prescribed medications to help with the symptoms and reduce any further damage to the rest of the heart. Again, it is really important that you take your medications as prescribed and talk with your doctor if they don’t agree with you. Never stop your medications without talking to your doctor [1] [10].

How do we fix heart valves?

Surgery is the answer. Your heart valve can either be repaired, or it can be replaced with an artificial valve instead. There are different types of replacement valves, some are made from metal, others are made from the hearts of animals such as pigs or cows. There is also the question of how the surgery is done. We can do open heart surgery in order to either repair the valve or remove the old valve and replace it. But sometimes, the valve can be repaired or replaced through a technique called a Percutaneous Valve Procedure, a type of keyhole surgery. This is less invasive than open heart surgery. It is all done through tubes that are inserted into your heart via an artery or vein in your leg. It is only suitable for certain types of valve disease [11].

Which type of surgery, or the type of valve replacement that you have depends on many different factors, the most important being the type or severity of the valve abnormality, but can also include patient choice, your age and whether you have other medical problems, to name a few. The most important thing about choosing which one is best for you is to have a detailed conversation with your doctor, discuss all the options, the pros and cons and make an informed decision together.

After valve surgery, of any kind, you will usually have medications to take to help keep the new valve healthy and working properly, and some medications to help the rest of your heart to recover. Again, it is really important that you take your medications as prescribed and that you don’t stop taking them without talking with your doctor first [11].

Life after valve surgery is different for everyone, some return completely to normal, others have to change some aspects of their lives. The recovery period can be a few weeks to months. Remember that everyone is different and every journey is unique.

Here are some further resources:

https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/conditions/heart-murmurs

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/echocardiogram/

www.livingwithvalvedisease.org

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/mitral-valve-problems/

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/aortic-valve-replacement/whyitsdone/

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng208

| [1] | British Heart Foundation, “Heart Murmurs – causes, symptoms & treatment,” [Online]. Available: https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/conditions/heart-murmurs. [Accessed 17 July 2022]. |

| [2] | Wikipedia, “The Heart,” [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heart. [Accessed 17 July 2022]. |

| [3] | H. Jonsson, E. Magnusdottir, H. Eggertsson, O. Stefansson, G. Arnadottir, O. Eriksson, F. Zink, E. Helgason, I. Jonsdottir, A. Gylfason, A. Jonasdottir, A. Jonasdottir, D. Beyter, T. Steingrimsdottir, G. Norddahl, O. Magnusson, G. Masson and B. Halldorsson, “Differences between germline genomes of monozygotic twins,” Nature Genetics, pp. 53, 27-34, 2021. |

| [4] | E. Mejia and S. Dhuper, “Innocent Murmur,” StatPearls Publishing, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507849/. [Accessed 17 July 2022]. |

| [5] | D. J. Sahn and B. C. Maciel, “Physiological Valvular Regurgitation,” Circulation, vol. 78, no. 4, pp. 1075-10877, 1988. |

| [6] | C. Rostagno, “Heart valve disease in elderly,” World Journal of Cardiology, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 71-83, 2019. |

| [7] | M. Klein and A. Wang, “Infective Endocarditis,” Journal of Intensive Care Medicine, vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 151-163, 2016. |

| [8] | J. J. Miner and A. H. J. Kim, “Cardiac manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus,” Rheumatic Diseases Clinics of North America, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 51-60, 2014. |

| [9] | J. Ternacle, N. Cote, L. Krapf, A. Nguyen, M. Clavel and P. Pibarot, “Chronic Kidney Disease and the Pathophysiology of Valvular Heart Disease,” The Canadian Journal of Cardiology, vol. 35, no. 9, pp. 1195-1207, 2019. |

| [10] | K. Maganti, V. Rigolin, M. E. Sarano and R. O. Bonow, “Valvular Heart Disease: Diagnosis and Management,” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, vol. 85, no. 5, pp. 483-500, 2010. |

| [11] | NICE, “Heart valve disease presenting in adults: investigation and management,” National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2021. |

Leave a comment